Co-authored with Tom White from Stonks and Ram Ben Ishay from the VC Podcast

Venture Capital has existed as a discrete asset class for over seventy years now.

A great deal has been written about what constitutes Venture Capital and what does not (including by Tom White) in these seventy years. Though many different things to many different people, Justice Potter’s famous dictum in Jacobellis v. Ohio works for our purposes: “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.”

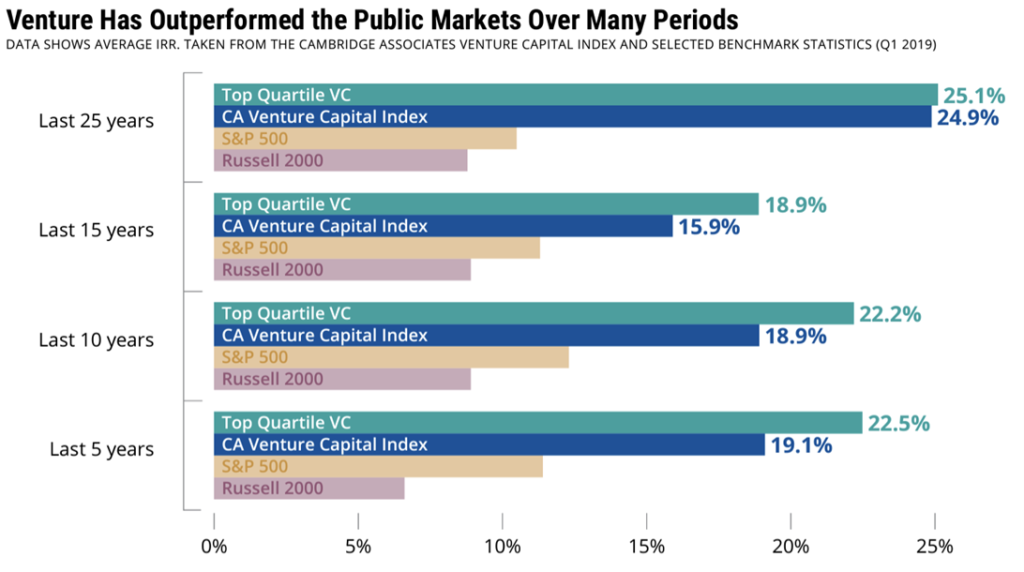

Despite these various definitions, one consistent feature has been written, spoken, read, and heard about Venture Capital: its tremendous outperformance over the last twenty years.

The data is irrefutable regardless of timeframe: over the last five, ten, fifteen, and twenty-five years, top quartile U.S. Venture Funds have generated the highest returns of any major, institutionally-backed asset classes

Because of this, very many podcasts and blog posts have sung Venture’s praises. This post will not pile on here.

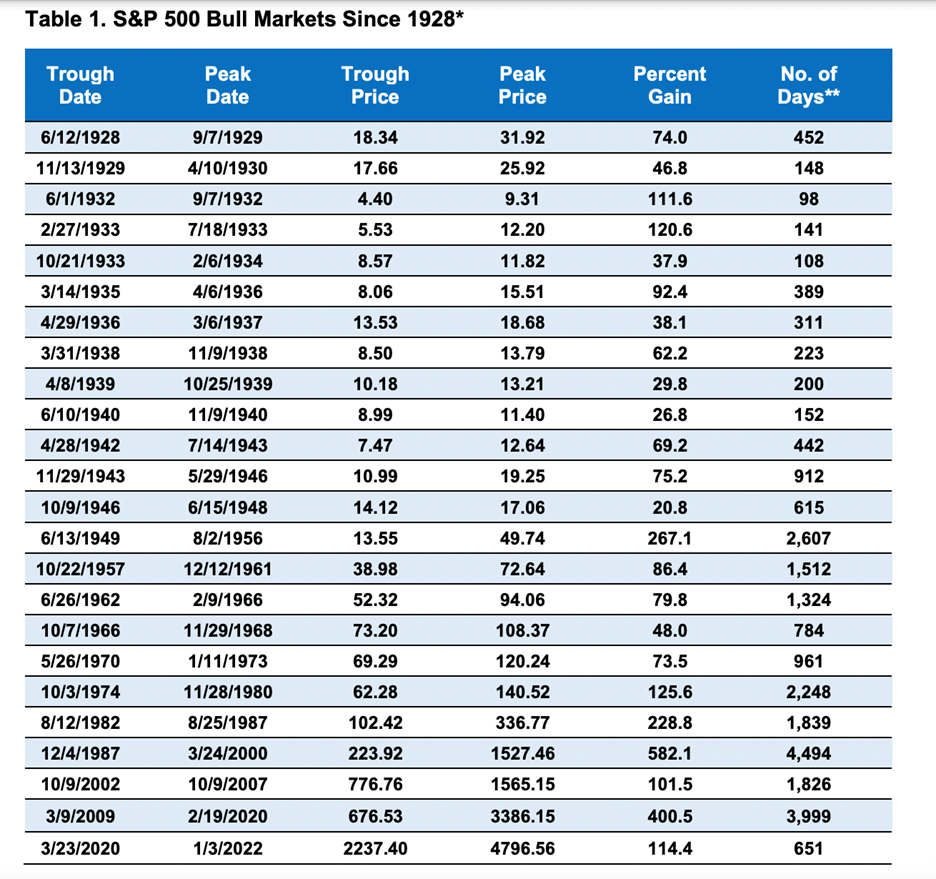

Interestingly (and perhaps conveniently, mind you), they all elide over a rather inconvenient truth: a great deal of this outperformance has coincided with arguably the greatest bull run in US history.

Given iffy economic forecasts, turbulent markets, and the looming threat of a recession, this begs two questions. Phrased generally: Did this rising tide lift all boats? More specifically: How does Venture Capital perform in periods of economic decline?

Show Me the Money Data!

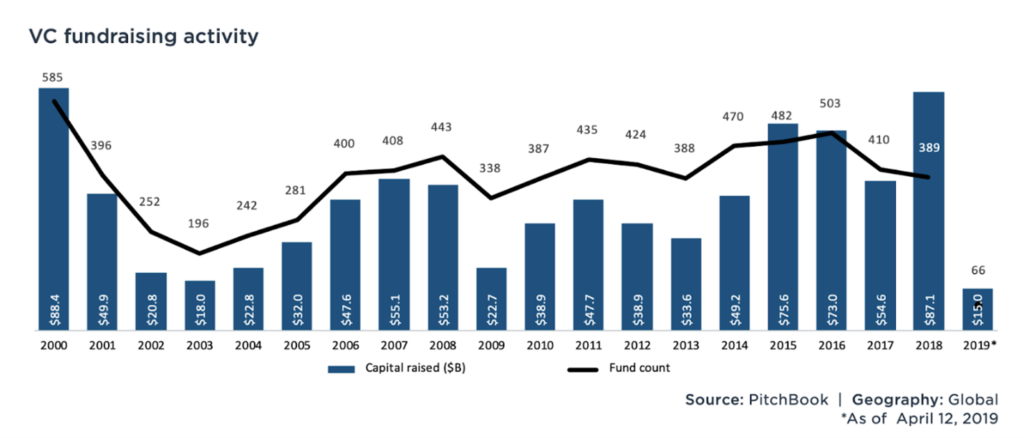

Unfortunately, measuring the performance of Venture Capital is a bit more challenging than conducting a similar analysis for public equities. For instance, although some data can be traced back to 1946, the Venture Capital of Georges Doriot and Don Valentine looks very different from that of Marc Andreessen and Mary Meeker. Not to mention, the nearly thirty-five-year period from 1946 to 1979 resembles mere creek when compared with the twenty-first century’s inundation of capital.

Because of this, a middling amount of data exists from that period. Similarly (and unfortunately), data regarding Venture Capital performance from the 1980s is shockingly spotty. In order to maintain data integrity and sound analysis, the below analysis focuses solely on the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009. No matter, we’re making lemonade with these lemons. Let’s get into it.

Recessions Make It Rain

Put simply, the Global Financial Crisis produced some of the best Venture Capital vintage years in modern history. A great deal of this value accrued to those GPs and LPs who deployed capital during the crisis’ nadir.

Per the table to the right, Venture Capital performance leading up to the recession was lukewarm. Both during and after the recession, however, performance really 🔥heats up 🔥

Though perhaps initially counterintuitive, upon reflection, some of the strongest performing companies of our generation—Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Pinterest, Snowflake, Slack, Square, Cloudera, Yammer, and many more – emerged and received funding during this downturn.

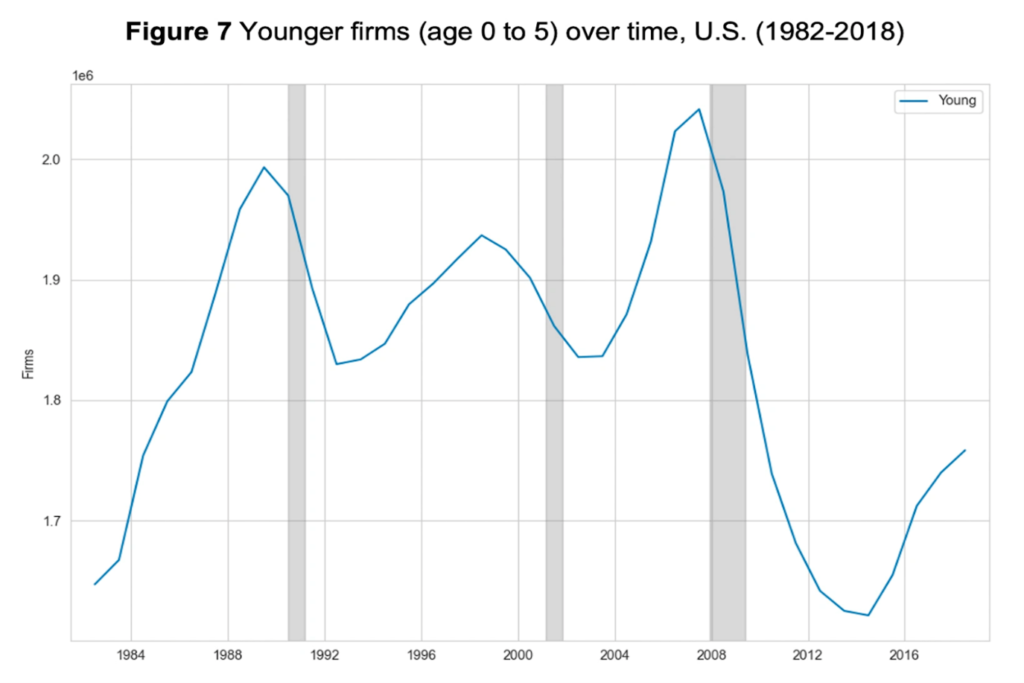

Looking at company formation data, the creation of these eventual winners equally spans a lengthy timeline. In fact, it is distributed almost equally before, during, and after the crisis. This supports the notion that good companies materialize through all sorts of financial climates, both good and bad.

Interestingly, the same conclusion does not hold true for the 2000 dot-com bubble. During this downturn, Venture Capital firms had some of the worst returns in history. Even top-quartile funds had single-digit IRR for their 2000-2002 vintages.

So much for a clean through line. What gives?!

Why Do Some Startups Born in Recessions Perform so Well?

Before answering, story time!

When Itamar started his venture career in late 2010 as a junior investment professional, the entrepreneurial ecosystem was still in shock after the 2008 crisis. Despite this, both time and luck were on his side; he was fortunate to have a front-row seat to the funding of some massive VC outcomes during this period. SentinelOne, Honeybook, and LendingClub are just a few that come to mind.

Though companies founded during recessions have a much harder time raising capital, they do benefit from three key advantages:

1) A Focus on Financial and Operational Discipline

Unlike the companies formed in the last three to five years, recession-born businesses must be more customer- and revenue-focused in order to survive. In these environments, founders sprint to build a self-sustaining business because they cannot rely on the safety net of Venture Capital to rescue them. Many aim to become default alive as soon as possible. Those that do not—or cannot due to poor unit economics or lack of product-market fit—seldom make it out of these periods alive.

This transcends the quantitative.

Good companies formed during bad times seem to instill a uniform “tighten-the-belt” ethos when it comes to controlling expenses and cash flow, building sustainable unit economics with quick cash recovery cycles in order to stay default alive. When executed correctly, these upstarts will grow into more efficient, robust businesses.

2) Less Competition

In times of crisis, fewer mavericks take the entrepreneurial leap and bigger companies retreat from new vertical expansion. These complementary forces drastically shrink the competitive landscape.

In fact, during the most recent tech bubble (i.e. 2018-2021), there seemed to be far too much money chasing far too few quality businesses.

Like weeds, bad, buzzy ideas proliferated and sucked precious capital from good businesses. Driven by FOMO and behavioral contagion, new, sexy ideas attracted the attention of entrepreneurs and VCs alike. This is the barren soil that competition produces; namely, an environment that makes it extremely difficult to produce a singularly-dominant, fast-growing, healthily-operated company.

3) Talent Acquisition Becomes Easier

During a recession, companies recruit a great deal less. Look no further than recent headlines from Meta, Google, and other giants about current/forthcoming hiring freezes.

Such an environment makes it far easier for David (i.e. startups) to hire talent both from Goliath (i.e. established tech companies) and Fellow Davids (i.e. other startups).

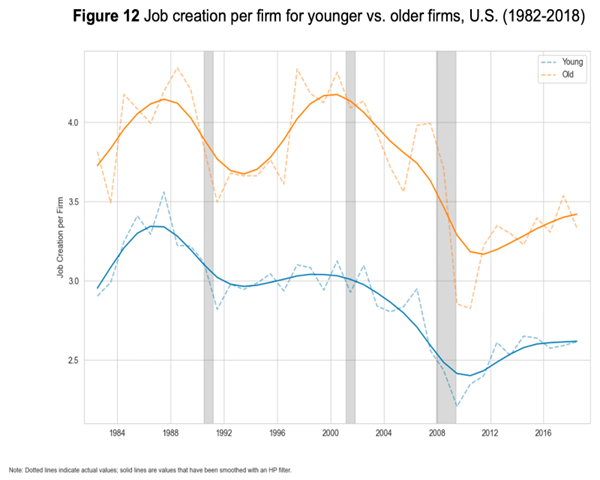

The below table showcases the cyclical oscillation of job creation by comparing younger and older firms over the last twenty years. During the Great Financial Crisis, job creation slowed by over 50%.

What’s Venture Capital Have to Do with It?

Venture Capital’s beauty derives from its focus on not what is, but rather what could be. As Sebastian Mallaby wrote in Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

Of course, investing in what is categorically impossible is a waste of resources. But the more common error, the more human one, is to invest too timidly: to back obvious ideas that others can copy and from which, consequently, it will be hard to extract profits.

As such, VC is an asset class focused on the long term—more interested in generational paradigm shifts than instantaneous profit extraction.

This is not a bug, but an invaluable feature. Because of this, at its earliest stages – Pre-seed, Seed, and Series A – VC is inherently anti-cyclical. Just think: companies into which Pre-seed investors deploy capital will reap potentially-mammoth rewards not in five to ten months, but in the subsequent economic cycle, five to ten years from now.

It’s worth mentioning that Later-Stage VCs tend to be much more sensitive to economic cycles due to their focus on sufficient capitalization for survival or near-term exit opportunities for liquidity. In recessions, exit timelines become muddled and can be shorter than the time horizon at which late-stage and pre-IPO funds tend to invest.

That said, our focus is on VC’s earliest stages. During recessions, early-stage investors benefit from:

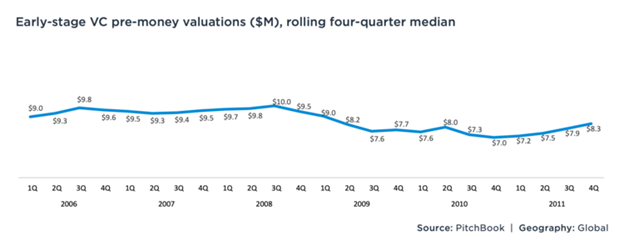

Lower valuations

In recessions, deals become far less competitive. Because of this, it becomes easier to win allocation into high-quality deals (i.e. those that can return a fund and lead to venture-sized outcomes).

Less Market Competition

As dealflow declines, so too does the pace of capital deployment. This forces VCs to focus more on proper deal due diligence before writing sizable checks. As is said, slow is smooth and smooth is fast.

Though not in the interest of predicting the future, August 2022 is rife with trends that seem to portend recession.

For example, in Q2 2022 Angel & Pre-seed deal activity has fallen ~30% QoQ:

Caveat Emptor and do with that information what you will.

History shows some of the best opportunities come in bad times, not good ones. Though we’re not in the business of prediction here at Recursive Ventures and Stonks, in the words of Lord Byron: “The best prophet of the future is the past.”

Put simply, if public/crypto market turmoil persists, early-stage valuations may well drop ~30% or lower (i.e.below levels seen merely a year ago!).

If that happens, don’t run out of the store when there’s a discount. You would do well to heed Warren Buffet’s advice to be greedy when others are fearful.

Who knows? Such greediness may provide a generational opportunity to invest in quality businesses at bargain prices.

Come along for the ride — we hope to see you on the moon. 🚀

N.B. Investing is a risky endeavor. Investing in startups is particularly risky. Nothing herein constitutes financial advice.